Sugar's Sour History and its Symbolic Power in Artworks

Posted 05/06/2024, originally written in 2021

It's almost summertime, and of course that means ice cream, popsicles, delicious frozen margaritas, and other cold sweet treats. As I eat way too much sugary food once again this summer, I am reminded of the German traveler Paul Hentzner's description of Queen Elizabeth I from 1578 - chiefly that her teeth were black, as many English people's seemed to be, from the consumption of sugar.1 I am also reminded that while it is readily available now, it was once a luxury good, and that luxury in Europe and British America came with a steep price - human lives.

Sugar cane made its first appearance in the Americas in 1493, when Christopher Columbus brought it over from the Canary Islands - Spanish territory at the time. It was grown first in Spanish-controlled Santo Domingo, now the capital of the Dominican Republic, and was shipped from there back to Europe starting in 1516.2 Enslavement of the indigenous peoples and of Africans began almost immediately after Europeans settled, and they were set to work on sugar mills and plantations.3 As sugar production spread from country to country in Europe, more and more islands in the Caribbean became production hotspots for sugar cane, and more and more enslaved Africans were brought over to produce it.

William Clark, Interior of a Boiling House on Delap's Estate, Antigua, 1823.

Meanwhile, in Europe, sugar was being consumed more and more readily as it was produced in greater and greater quantities. As its production increased, its prices decreased, making it more readily available to more people. By the 1680s, sugar was becoming a common good among the upper middle classes as well as the aristocracy.4 It was a sweetener in tea and chocolate, it was used in baked goods, and it was swiftly becoming a dietary staple.

German School, Still Life of a Bowl of Strawberries, Standing Cup, Bottle of Rose Water, a Sugar Loaf, and a Box of Sugar, 1680.

Artworks began depicting sugar and foods made with sugar as it became a more familiar item in Europe, and, like other luxury goods in Europe, it was included in these artworks as symbols of status, wealth, and beauty. Confection itself became its own popular art form. As sugar became more abundant, the uber-wealthy began purchasing greater amounts of sugar and using it to create massive and intricate sculptures. These sugar sculptures, first popular in late Renaissance Italy, were purely decorative status symbols. They indicated the commissioner's wealth and their ability to purchase massive quantities of sugar without consuming it.5

Triumphal Sculptures, 1680s.

However, behind the beauty of these sculptures, the artistry of confection, and the commodification of sugar, we can't forget the people who were forced to produce these massive quantities of a luxury they would never taste. Slaves on sugar plantations worked anywhere from 10 to nearly 24 hour shifts a day, and the mortality rates on these plantations were staggering. The majority of enslaved people never made it past their thirties or early forties, and less than half of enslaved children born into slavery made it to their fifth birthday.6 The history of sugar is soaked in the blood of hundreds of thousands of enslaved and oppressed people.

Created within the Domino Sugar Refinery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Kara Walker's Marvelous Sugar Baby installation was an homage to all of the African people enslaved for the purpose of sugar production. The Domino Refinery, built in 1884, received its sugar from production centers in the Caribbean until its closure in 2004.7 Walker's Marvelous Sugar Baby, made entirely out of refined white sugar, depicts a steroptypical "mammy" figure in the position of a sphinx, her nude body arranged in a provocative position to represent the rape and abuse of enslaved black women. The artwork draws attention to the backbone of sugar production and the reason for its profitability - slavery.8

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or, The Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014.

Don't get me wrong, I still enjoy eating sugary foods, and today, sugar is not produced from the hard labor of enslaved and oppressed people. It is, however, important to understand sugar's unpleasant history and acknowledge the complacency of the people overseas who allowed the atrocities on sugar plantations to continue to happen so they could have their sweets.

1. Paul Hentzner, Travels in England during the Reign of Queen Elizabeth; with Fragmenta Regalia, ed. by Henry Morley (Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg, 2015), 46. ↩

2. Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), 32.↩

3. Rosa Elena Carrasquillo, "The Creation of the First Spanish Colonial Landscape in the Americas, Santo Domingo, 1492-1548." Antipode , no. 36 (July 2019): 68-71. doi: 10.7440 /antipoda36.2019.04↩

4. Mintz, Sweetness and Power, 38-39.↩

5. Mintz, Sweetness and Power, 88-89; Ewa Kociszewska, “Displays of Sugar Sculpture and the Collection of Antiquities in Late Renaissance Venice”, Renaissance Quarterly 73, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 445. doi:10.1017/rqx.2020.2.↩

6. A. Meredith John, “Plantation Slave Mortality in Trinidad”, Population Studies 42, no. 2 (1988): 180-181.↩

7. Raquel Kennon, “Subtle Resistance: On Sugar and the Mammy Figure in Kara Walker’s A Subtlety and Sherley Anne Williams’s Dessa Rose”, African American Review 52, no. 2 (Summer 2019): 144. doi:10.1353/afa.2019.0025.↩

8. Ibid, 143-144.↩

Japanism and the Birth of Art Nouveau

Posted 05/06/2024, originally written in 2022

Asian countries have been a source of fascination in Western Europe for centuries, ever since the Italian explorer Marco Polo traveled down the Silk Road in the thirteenth century. His tales of the Far East sparked the establishment of overseas trade route to Asia in search of luxuriant spices and materials, and eventually the building of massive trade empires. Over the centuries, these trade routes brought spices, tea, fabrics, furniture, porcelain, fashion, and art to Europe from India, China, and Japan, until Japan closed its borders in 1638 to avoid Europe’s religious and commercial influences.1 European visual and decorative arts such as clothing, ceramics, and furniture evolved to emulate those brought in from Asia. This is where the word chinoiserie originated – derived from the word chinois, or “Chinese” in French, it refers to the Asian-influenced decorative arts popular in Europe from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Chinoiserie referred to items such as detailed, hand-painted wallpaper, fabric and textile designs (Fig.1), clothing like the banyan and similar dressing-gowns (Fig.2), ornamented furniture and folding-screens (Fig. 3), and blue-painted porcelain (Fig. 4).2

Figure 1. Banyan, 1735-40, silk. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 2. Dress, 1760s, silk, metal thread. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 3. René Dubois, Drop-Front Secretaire (Secrètaire à Abattant), 1770-75, painted and varnished oak, veneered with European lacquer, mahogany, purplewood, gilt-bronze mounts. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 4. Plate, 1750-60, tin-glazed earthenware. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Eventually, however, Britain staged the early 19th-century Opium Wars in China, subjugating it to foreign powers and leading to economic weakness and uprisings. These events would cause a gradual collapse of the Qing Dynasty and begin a new wave of industrialization and modernization, smothering much of its exotic appeal.3 Concerned with the British trade presence in Asia after the Opium Wars, United States Naval Commander Commodore Matthew Perry convinced Japan to once again open their borders to trade in 1854.4 Once trade was open, European nations also seized the opportunity to trade with a new Eastern country and Japanese imports flooded Europe and the United States, encouraged by the 1868 opening of the Suez Canal.5 Within a few short decades Orientalism had shifted its focus almost entirely onto Japan, opening the West to new artistic and cultural influences. In this essay, I intend to demonstrate how this shift in interest towards Japanese art and architecture helped to bring about the Art Nouveau movement in the West.

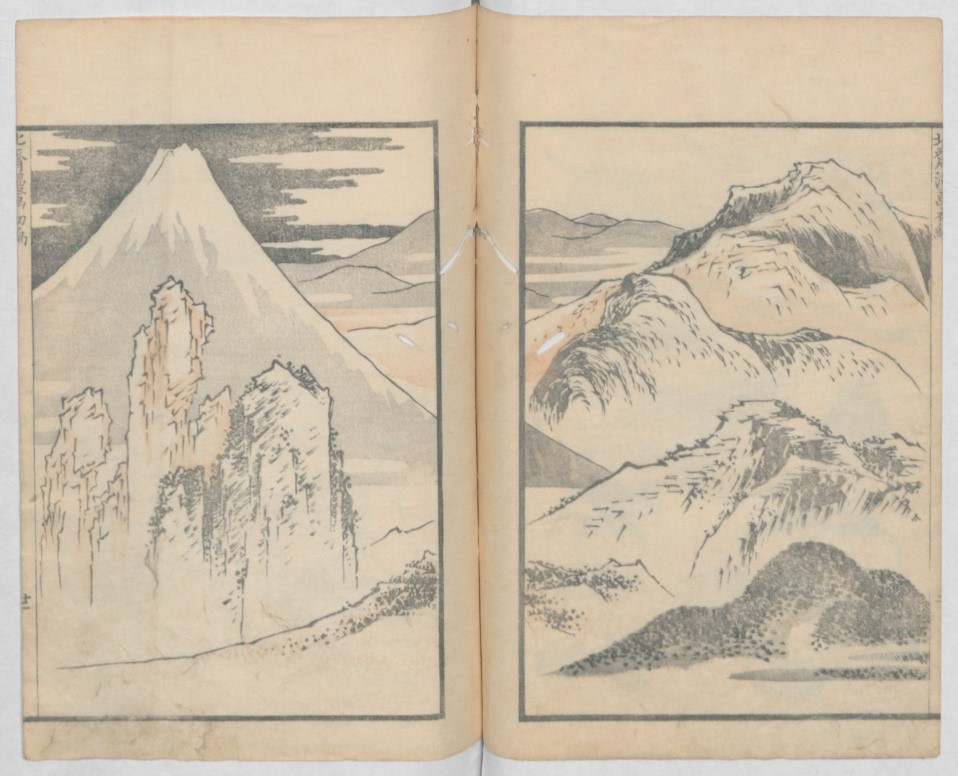

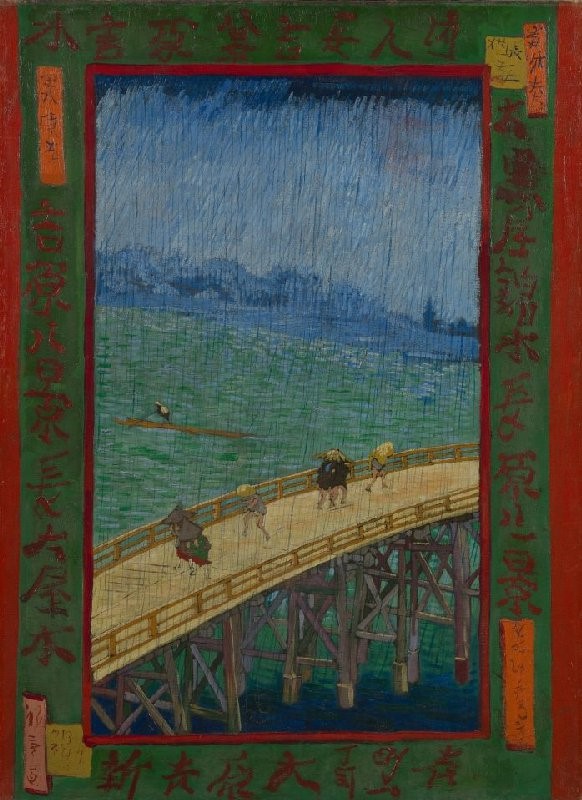

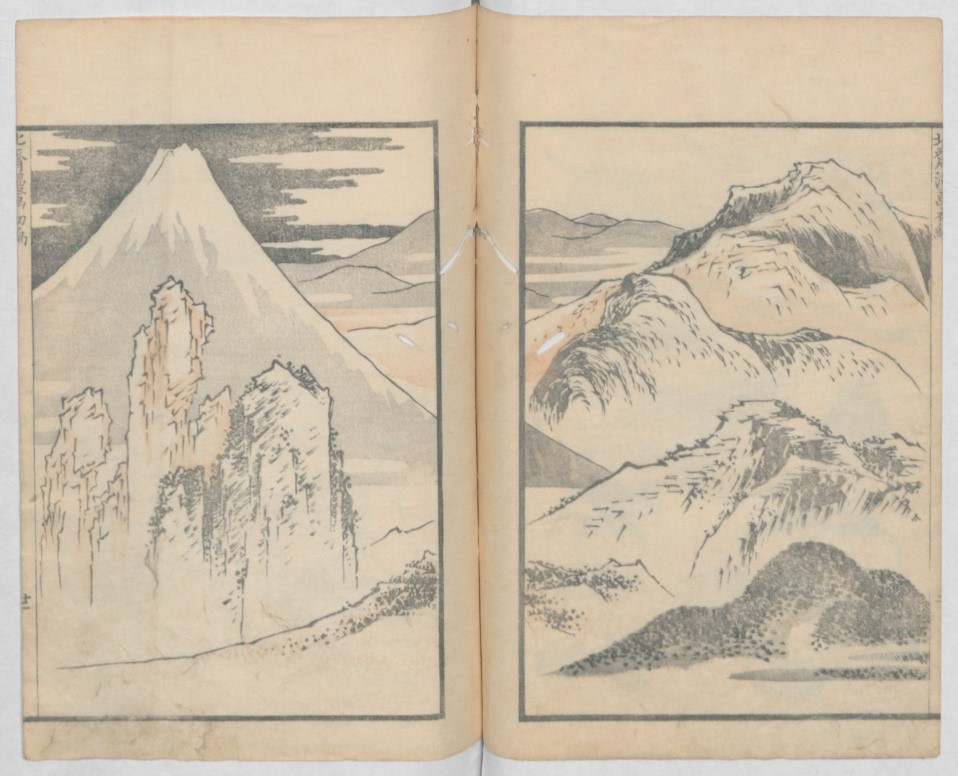

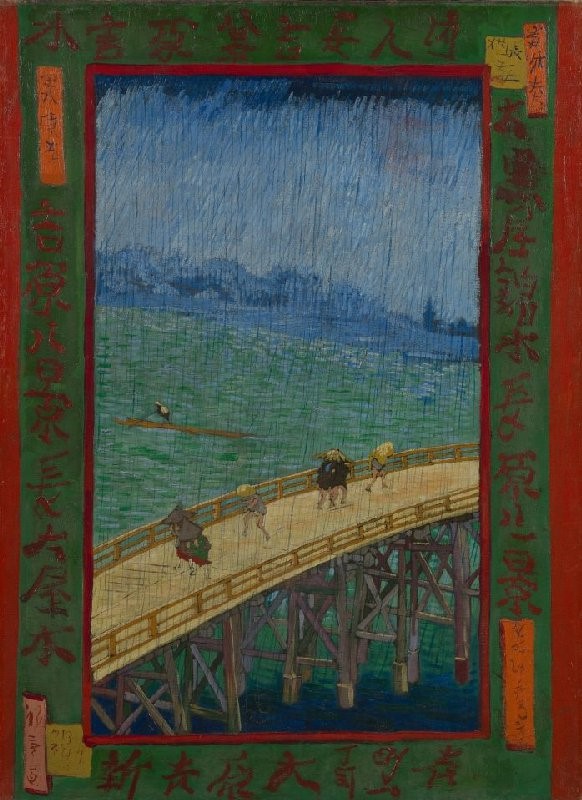

The first hints of Japanism, also known by its French moniker Japonisme, as an artistic movement took off in the 1850s after Japan began to export goods and art to Europe. It is debated when exactly Japanese art began to influence Western design, but it was first suggested in writing from 1905 that it started when French painter and ceramicist Felix Bracquemond found a volume of the Manga left in his workshop in 1856 by a fellow ceramicist.6 The Manga (Fig. 5) is a collection of Japanese woodcut-printed sketches done by Katsushika Hokusai, encompassing fifteen volumes and spanning in publication dates from 1814 until 1878, long after Hokusai had died in 1849.7 This discovery, as it were, would lay a foundation for the West’s near-obsession with ukiyo-e (or “pictures of the floating world”) woodcut prints, which first found their way to Europe as wrappings around porcelain imports. Before long, ukiyo-e was highly coveted by artists and art enthusiasts who made a hobby out of collecting them. These prints would inspire artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and other impressionists and post-impressionists throughout Europe to adapt the calligraphic line, simple color, and amorphous space of Japanese prints into their own artworks (Fig. 6).8

Figure 5. Katsushika Hokusai, spread from Random Sketches of Hokusai, 1814-1819, woodblock print, ink and color on paper. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 6. Vincent van Gogh, Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), 1887, oil on canvas. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

However, the Art Nouveau Movement was catalyzed – and the term popularized – by Siegfried Bing, a collector and seller of Japanese artwork, and of whom van Gogh and other post-impressionists were regular customers. Gabriel P. Weisberg details much about Bing in his article “Lost and Found: S. Bing’s Merchandising of Japonisme and Art Nouveau.” According to Weisberg, Bing was a member of the Japanese Societies in London and Paris, a collective who popularized and spread Japanism and the appreciation of Japanese art.9 While involved with these societies, Bing was able to connect with Hugues Krafft, a photographer, traveler, and collector who visited Japan in the 1880s. However, Krafft did not just collect Japanese artwork; he also purchased a Japanese home while visiting Japan and had it assembled in an authentically-designed Japanese garden just outside Paris by Japanese craftsmen. Krafft would live in the house, dress in Japanese clothing, and use it as an escape from society. The house, called Midori-no-sato, would eventually host the meetings for Japanese Society from Paris, where the members would also frequently wear kimonos.10

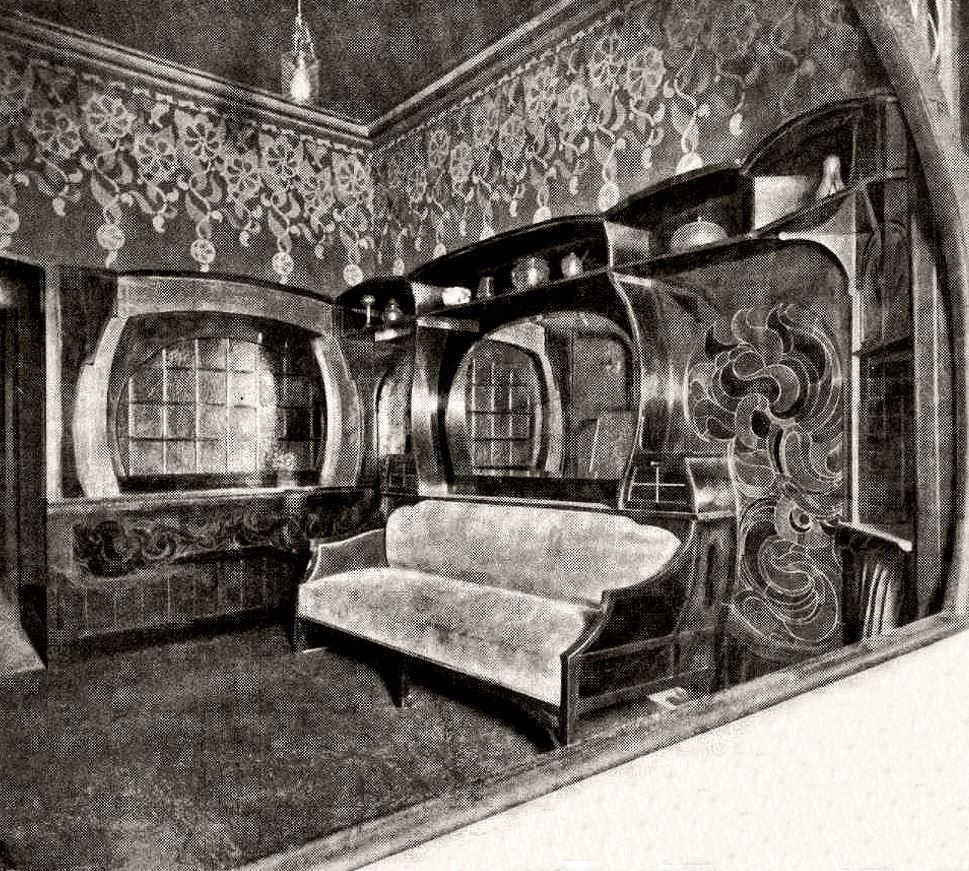

Bing's connections within the Japanese societies, including Henry van de Velde and Victor Horta, allowed him to build and open to the public his Salon of Art Nouveau in Paris in 1895. Before establishing the Salon, Bing had run other stores selling mainly Japanese objects, establishing connections with private collectors in an attempt to corner the market. His first shop selling Japanese items opened in 1878, but after traveling to Japan between 1880 and 1881, Bing opened up two more shops. His extensive collections allowed him to lend hundreds of ceramic pieces to a Japanese art exhibition in 1883, and by this time, he was widely known among artists and collectors as one of the best sources for acquiring Japanese art.11 With this new Salon of Art Nouveau, however, Bing hoped to introduce a new form of decoration and interior design to Western homes across the country, using his knowledge of Japanese art and his years of marketing experience. He believed that Japanese art was part of an art nouveau, a “new art,” that could change Western design forever. The Salon of Art Nouveau displayed proudly his vision of future homes, with cohesive interior designs, open plans, and Japanese-inspired ornamentation.12

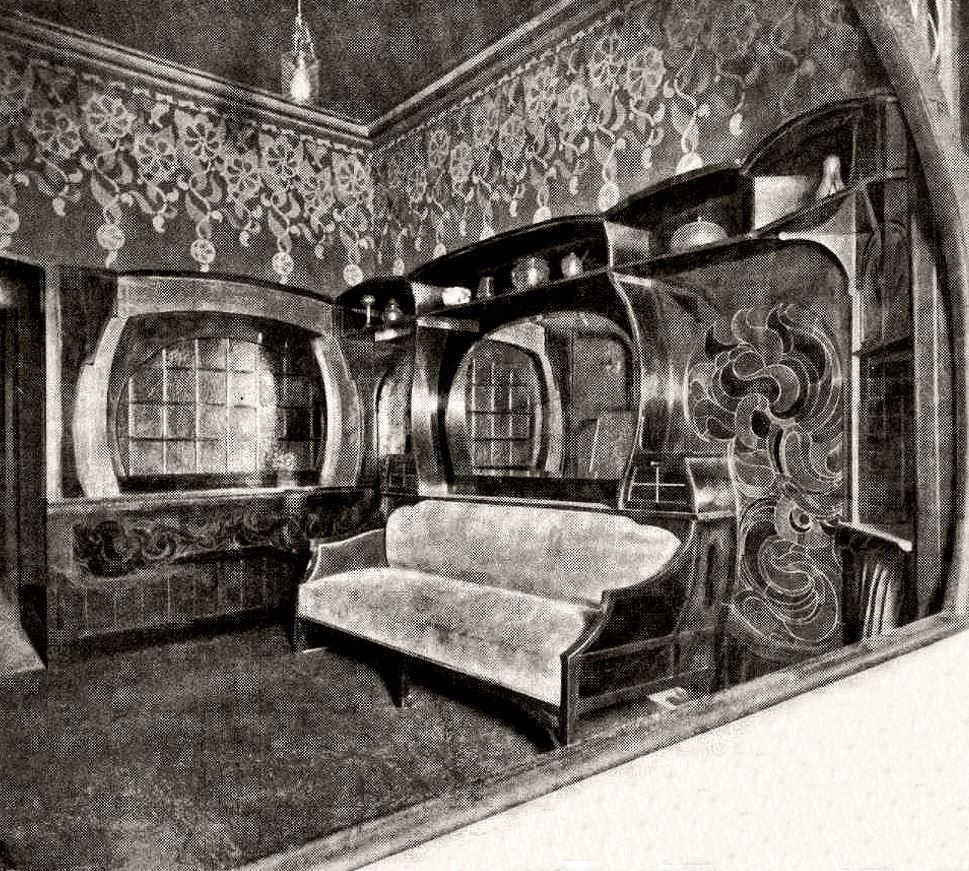

Bing’s marketing of Japanism and Art Nouveau kickstarted an architectural movement in Belgium stemming mainly from two of his artistic acquaintances: Henry van de Velde and Victor Horta.13 Henry van de Velde, an artist of all media, was drawn to the paintings of van Gogh and emulated his use of line and form in his own paintings, believing that line is the driving force in art.14 This belief would carry over into his architectural exploits, where curvilinear forms would soften and embellish a design with an almost Rococo look (Fig. 7). Van de Velde’s fellow architect in Belgium was Victor Horta, who is known as one of the chief founders of Art Nouveau in architecture. Horta’s architectural designs, full of whiplashing vegetal ornamentation and soft, fluid forms, were influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, namely the designs of William Morris and Walter Crane, as well as the Japanese obsession sweeping across Europe – made popular in Belgium partially due to the socialist movement at the time needing a fresh visual appeal.15

Figure 7. Henry van de Velde, Smoking Room in the Salon of Art Nouveau, 1885. Paris, France.

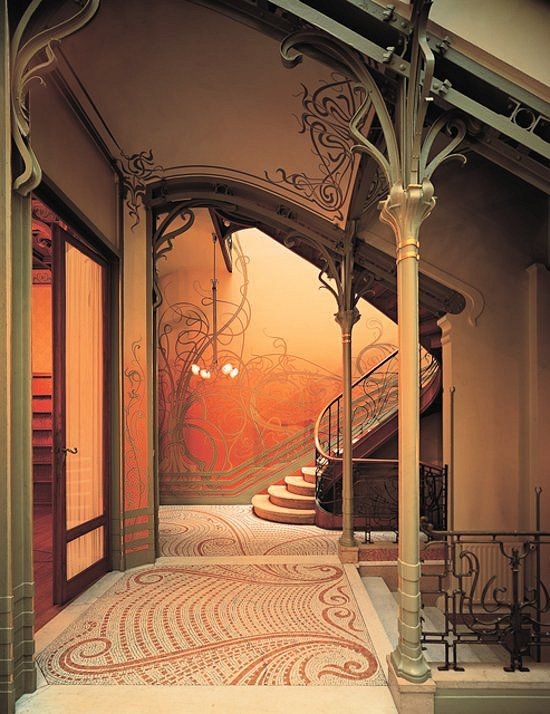

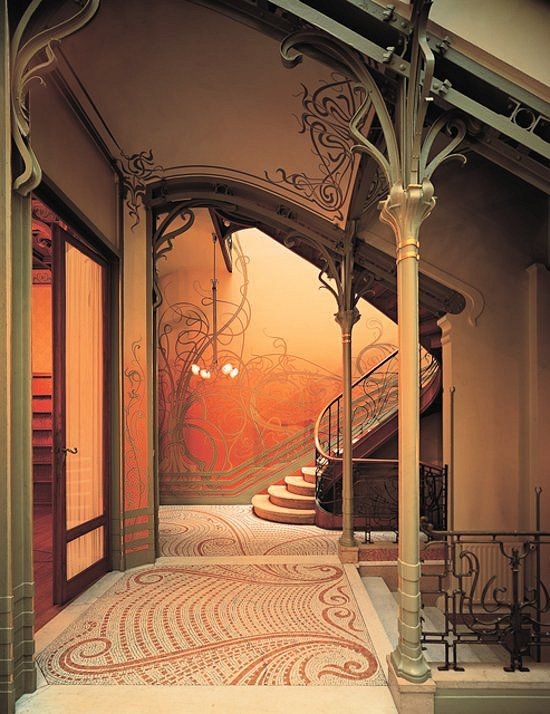

The Japanese influences on Horta via his connections with Bing as well as the influx of Japanese imports and the expansion of ukiyo-e-inspired impressionist paintings are best exemplified in his most famous project, the Hotel Tassel (Fig. 8). Most notable is the extensive ornamentation in the murals, mosaics, and exposed wrought-iron – the lines of Horta’s ornamentation (the “ligne Horta”)16 emulate the curved lines of a calligrapher’s brush. Much of this sweeping organic motion could be attributed to the arabesque, a gestural line found in much impressionistic artwork at the time and influenced in turn by the Japanese woodblock prints being collected and shared by those impressionists.17 The entire interior of the building appears intensely connected to nature - the iron columns stretching to the ceiling suggest a forest-like space, emphasized by the abstracted vine designs on the walls and in the mosaic of the floor within the entrance hall, along with the winter garden included by the staircase.18

Figure 8. Victor Horta, Hotel Tassel, 1892-93. Brussels, Belgium.

In Japanese culture, especially within the Shinto religion, there is an emphasis on an increased sensitivity to nature and the natural world, and therefore the architecture in Japan expresses this idea. The sukiya style of architecture in Japan, popularized in the 16th century, makes physical the harmony of the interior and exterior of a building and its integration into nature.19 The popularity of Japanese prints had an influence on the Hotel Tassel's floor plan as well, notably the compositional asymmetry and a simplification of natural shapes within those prints.20 The non-Euclidean floor plan, removing itself from the traditional, classical idea of space, also emulates a Japanese understanding of architecture – the plan is much more open and flows from room to room comparable to the spatial organization of a Japanese house.21 Horta’s architecture, like the impressionists, broke away from the rigid classical tropes found in architecture and design and forged a new path.

Meanwhile, British scholars, scientists, and artists were traveling to Japan and coming back bursting with new information. Many came back stating, and even writing extensively, that Japan had no or very little architecture — chiefly Rutherford Alcock, the British Minister to Japan.22 However, Edward S. Morse, a zoologist, was so fascinated with Japanese architecture and so worried that westernization would render it lost forever that he wrote a text on his return titled Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings in 1885, detailing the construction of a Japanese dwelling from the roof to the floor plan, as well as their gardens, urban buildings, rural buildings, and every room within the dwelling.23 This book, along with the paintings of Whistler and other post-impressionists, circulated throughout Britain before finding a fast home in Scotland – notably Glasgow, the home of architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh.24

While Mackintosh’s designs are not usually the first to come to mind when Art Nouveau is mentioned, they still emulate much of the ideals of the movement, as well as the Japanese influences. As a key player in the Celtic Revival movement at the time, Mackintosh used Japanese architectural features to enhance and modernize the Scottish architecture making a comeback in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.25 His architecture is much more linear and geometric than most other Art Nouveau architects, but it suggests a level of rusticity and cohesion with nature that recalls Japanese ideals presented through their own art and architecture and articulated through Morse’s text. A good example of these Japanese features combining with the Scottish Revival is his Willow Tea Rooms designed in 1903 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Willow Street Tea Rooms, 1903. Glasgow, Scotland.

In her book Easel to Edifice, Judith Stone describes the history of the Japanese tea house and its primary features — the Tai-an, a sixteenth-century tea house built by Sen no Rikyo, became the model for most Japanese tea houses afterwards, and much of its architectural style, called sukiya, was integrated into Japanese architecture. Its most prominent details were a simple, rustic wood structure, papered windows to filter and dim sunlight, unpolished beams, and a warm, intimate atmosphere to stimulate peace, conversation, and closeness.26 Mackintosh would have had access to this design knowledge through the ukiyo-e prints he collected, the photographs brought back from Japan, and, most importantly, the copy of Morse’s text which he had in his possession.27 In Mackintosh’s tea rooms, the geometric lines and simple usage of color can be compared to those same elements in ukiyo-e prints, and the open floor plan suggests the same spatial awareness evident in Japanese architecture. The façade, while deceptively simple, is slightly curved to indicate an organic line, and the gridded windows directly reference the square papered windows found in traditional Japanese tea houses (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Utagawa Yoshikazu, Foreigners Enjoying Children's Kabuki at the Gankirō Tea House, 1861, woodblock print, ink and color on paper. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As Art Nouveau bloomed in Europe, Japanism spread to the United States as well with the help of impressionist and post-impressionist paintings and Morse’s text. It made itself known especially in Chicago, where new architectural ideas were blossoming in the Chicago School. In Chicago Art Nouveau, the Orientalist details manifest themselves less through ornamentation and more through structural features. Louis Sullivan of Adler and Sullivan demonstrated some Japanese characteristics in his architecture, including horizontal eaves reminiscent of the roof of an East Asian temple and banked windows,28 but the true embodiment of the Japanese influence on Chicago Art Nouveau is Frank Lloyd Wright. Apprenticing first under the Japan enthusiast J. W. Silsbee, Wright eventually moved on to work for Adler and Sullivan until 1893.29 From Sullivan he learned the concept of “organic architecture,” which Sullivan had, in turn, derived from observing the Japanese Hoo-den building at the World’s Columbian Exposition there in Chicago in 1893.30 Beyond his mentors, Wright was almost certainly influenced at least in part by Morse’s Japanese Homes, which was the primary dissertation on Japanese architecture in the United States for decades once published.31 Wright also began collecting Japanese prints because

“…ever since I discovered the print Japan had appealed to me as the most romantic, artistic, nature-inspired country on earth. Later I found that Japanese art and architecture really did have organic character. Their art was nearer to the earth and a more indigenous product of native conditions of life and work, therefore more nearly modern as I saw it, than any European civilization alive or dead.”32

Wright was also a spiritual person and held much reverence for nature, even capitalizing the word in writing, and thus he could relate to the way the Japanese interacted with nature.33 This love for and relationship to Japanese art and culture made itself known through Wright’s architecture, especially in his home and studio, Taliesin East (Fig. 11). The building boasts strong horizontal lines throughout its design, recalling the flared roofs (irimoya)34 found on temples throughout East Asia and the gridded windows in Japanese tea rooms. The roofs are gabled and extend downward on all sides like irimoya as well. The eaves within also strongly suggest the rusticity found in Japanese builds. Its floor plan is a shining example of Wright’s rambling, asymmetrical organic architecture, inspired at least partially by non-Euclidian Japanese layouts. Its large, spacious rooms (Fig. 12) flow into one another with an appealing continuity, and the forms it creates are simple and geometric without seeming sharp. As a whole, it encompasses everything Wright found modern and interesting in Japanese art and architecture, while at the same time not copying any Japanese form or feature entirely.

Figure 11. Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin East, 1911. Iowa County, Wisconsin.

Figure 12. Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin East Interior, 1911. Iowa County, Wisconsin.

Orientalism and especially Japanism had a massive influence on the turning point of art and architecture in the Western world with Art Nouveau at the crux. As the Industrial Revolution was taking off, interest in China was dwindling, and the Romantic movement was growing stale, Japan opened itself to trade with the West at a crucial moment in history. From this act, among others, sprang the post-impressionists, the “whiplash” and arabesque lines, the non-Euclidean organization of space within a building, the freedom of asymmetry, integration of architecture with nature, and strong geometric and linear sensibilities in architecture and interior design. Though short-lived, the art and architecture of Art Nouveau mark the pivotal moment when Western design could begin to break free from the boundaries of classical architecture and artwork, all thanks to the popularity of Japanism in the mid-19th century.

1. Ceferina Gayo Hess, “Silk Road,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Hackensack: Salem, 2020); "Opening of Japan," in Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History Vol. I, ed. Thomas Carson and Mary Bonk (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999), 505-506.↩

2. Marie Riccardi-Cubitt, “Chinoiserie,” in Grove Art Online (2003).↩

3. Jiang Yonglin, "Qing Dynasty," in Encyclopedia of Modern Asia Volume 5, ed. Karen Christensen and David Levinson (New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2002), 27-31.↩

4. “Opening of Japan,” 505.↩

5. Clay Lancaster, The Japanese Influence in America, (New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc, 1963), 22.↩

6. Phylis Floyd, “Japonisme,” in Grove Art Online (2003); Lancaster, Japanese Influence, 33.↩

7. Masato Naitō, "Katsushika Hokusai," Grove Art Online (2003).↩

8. Lancaster, Japanese Influence, 33; Judith E. Stone, Easel to Edifice: Intersections in the Principles and Practice of C.R. Mackintosh and Henry Van De Velde (Champaign, IL: Common Ground Research Networks, 2018), 128-130.↩

9. Gabriel P. Weisberg, “Lost and Found: S. Bing’s Merchandising of Japonisme and Art Nouveau,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 2.↩

10. Weisberg, "Lost and Found.”↩

11. Stone, Easel to Edifice, 124-132.↩

12. Weisberg, "Lost and Found.”↩

13. Martin Eidelberg and Suzanne Henrion-Giele, “Horta and Bing: An Unwritten Episode of L’Art Nouveau,” The Burlington Magazine 119, no. 896 (1977): 747.↩

14. Stone, Easel to Edifice, 64, 82.↩

15. Tsihlias, George. “Victor Horta: The Maison Tassel, the Sources of Its Development.” Canadian Journal of Netherlandic Studies 17, no. 1/2 (1996): 108–28; Maurice Culot, “Belgium: Red Steel and Blue Aesthetic” in Art Nouveau Architecture, ed. Frank Russell (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1979) 92-93.↩

16. Tsihlias, ”Victor Horta,” 109.↩

17. Ibid, 116.↩

18. Charlotte Ashby, “Nature and New Forms: Art Nouveau at the Fin-de-Siècle,” Groniek, no. 219 (July 2019): 171–86. doi:10.21827/groniek.219.36991.↩

19. Judith E. Stone, Easel to Edifice: Intersections in the Principles and Practice of C.R. Mackintosh and Henry Van De Velde (Champaign, IL: Common Ground Research Networks, 2018), 104.↩

20. Tsihlias, ”Victor Horta,” 119.↩

21. Ibid, 112-113.↩

22. Anna Basham, “The Changing Perceptions of Japanese Architecture 1862-1919," in Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits, Vol. VII, ed. Hugh Cortazzi (Folkstone, Kent, UK: Brill, 2010), 487.↩

23. Basham, “Changing Perceptions," 495-496; Lancaster, Japanese Influence, 66-67.↩

24. Ibid, 496; Olive Checkland, Japan and Britain After 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges (New York: Routledge, 2003), 116.↩

25. Michael Shaw, The Fin-de-Siècle Scottish Revival, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020, 135. ↩

26. Stone, Easel to Edifice, 103-104.↩

27. Basham, “Perceptions of Japanese Architecture, 497; Stone, Easel to Edifice, 103-105.↩

28. Lancaster, Japanese Influence, 84.↩

29. Ibid.↩

30. Ibid, 84-85.↩

31. Ibid, 75; Kevin Nute, “Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Architecture: A Study in Inspiration.” Journal of Design History 7, no. 3 (1994): 177. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1316114. ↩

32. Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (New York: Duell, Sloane, and Pearce, 1942), 194; Lancaster 85. ↩

33. Stipe, Margo. “Frank Lloyd Wright and the Inspiration of Japan.” East-West Connections 4, no.1 (2004): 17.↩

34. Lancaster, Japanese Influence, 71. ↩

Let's Get This Bread: How the Ritualistic Consumption of Wheat Bread Upheld the Empire of the Catholic Church and Where it is Seen in Artwork

Posted 05/07/2024, originally written in 2021

The usage of wheat bread for the Catholic practice of the Eucharist has been a tool of power within the Catholic Church for centuries. The Eucharist, a ritual using wheat bread to symbolize the body of Christ and grape wine to symbolize his blood, is an ancient Christian ritual with a mystical side within the Catholic denomination and has evolved from the concept of a meal to a sacrament symbolizing the meal.1 One of the starkest depictions of this evolution can be seen in Fra Angelico’s The Last Supper (Fig. 1) painted in Florence in 1441. While most common Last Supper illustrations show Christ and the disciples sitting together around a table with some sort of meal spread before them, this fresco shows Christ leading his disciples in the Eucharist ritual the way the Catholic Church practiced it. Christ holds a goblet of wine and gives out small pieces of bread to his disciples, who bow their heads or kneel while receiving the sacrament.

Figure 1. Fra Beato Angelico, The Last Supper, 1441. Florence, Italy.

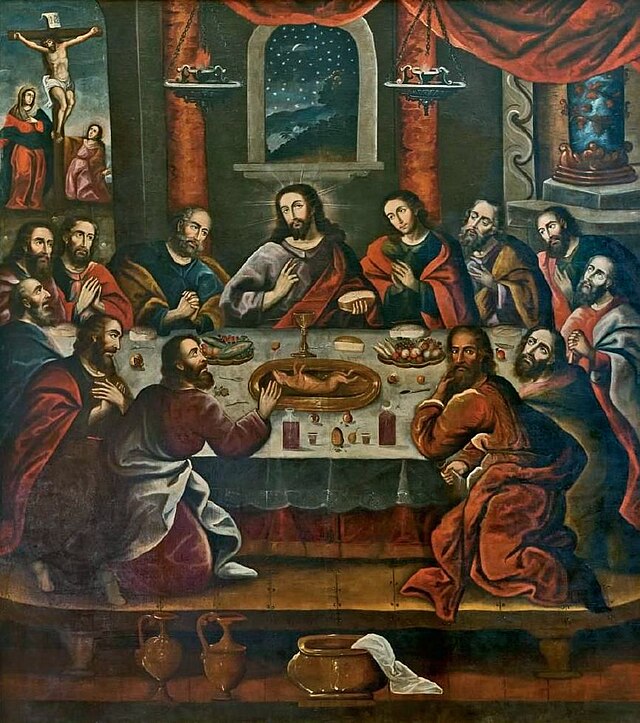

Another painting over a century later by Juan de Juanes, titled The First Eucharist, (Fig. 2) gives a similar impression, though it is nowhere near as literal as Fra Angelico’s. In The First Eucharist, Christ holds a thin white circular wafer – a replacement for loaves of wheat bread in many churches. In this painting, Christ is again distributing a modern version of the sacrament to his followers, instead of participating in what the actual Last Supper may have looked like. Both Juan de Juanes’ and Fra Angelico’s paintings give the viewer some insight into how sacred the Eucharist is as well as how powerful the person distributing the sacrament is by putting Christ directly in the place of the distributor. In the Catholic Church, the person distributing the sacrament is any ordained religious leader under the Pope, from a priest or bishop to the Pope himself. The ritual can also be performed at any time, in any place, in any church, by any ordained extension of the Pope’s authority, allowing for the unification of followers across the globe through one identical practice established under one authority.2

Figure 2. Juan de Juanes, The First Eucharist, 1562. Valencia, Spain.

The Eucharist has a mystical side to it as well – transubstantiation. Catholics believe, as reestablished during the Counter-Reformation at the Council of Trent in the mid-16th century, that during the performance of the Eucharist ritual, the wheat bread and the grape wine become the true flesh and blood of Christ, which are consumed by those participating in the ritual.3 However, it was established as early as the thirteenth century, if not earlier, that the bread had to be made of wheat and the wine had to be grape wine, for any substitution would not allow for transubstantiation to take place.4 This is where the empirical side of the Catholic Church truly began to take hold within the context of the Eucharist.

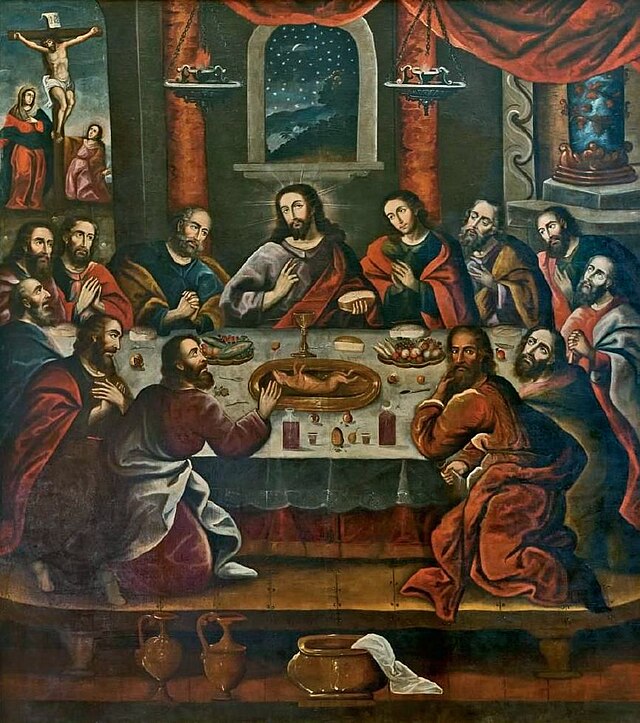

It was also around this time that conquistadors and settlers had found their way to the New World and had begun settling it in earnest, but to their disappointment and frustration, found that there were no grapes for wine and no wheat for bread in the New World. However, the sacrament required wheat bread, so wheat had to be imported and grown to allow for the rituals to continue, and the indigenous converts had to start using wheat for their bread instead of substituting with other grains.5 Thus began the agricultural colonization of the New World, which is why, in Marcos Zapata’s Peruvian version of The Last Supper (Fig. 3) painted in 1753, Christ and his disciples are depicted eating wheat bread, the only food on the table not native to Peru.6

Figure 3. Marcos Zapata, The Last Supper, 1748. Cuzco, Peru.

The distribution of the sacrament of the Eucharist through the power of the Pope and the requirement of the usage of wheat bread in the ritual helped to create a religious empire as the Catholic Church spread to every corner of the globe, creating its own colonies through the establishment of churches. Its followers all conformed, eventually, to the same ideologies, the same rituals and practices, the same beliefs and values, and the same submission to one all-powerful authority enthroned by God’s divine power.

1. William J Collinge, Historical Dictionary of Catholicism (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 151-152.↩

2. William J. Collinge, Historical Dictionary of Catholicism (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 152; Lawrence Cunningham, An Introduction to Catholicism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 133-134.↩

3. William J Collinge, Historical Dictionary of Catholicism (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 435-436.↩

4. Andrea Maraschi, “Wine, Bread, and Water, between Doctrine and Alternative. Norms and Practical Issues Concerning the Eucharist and Baptism in Thirteenth-Century Europe,” Revista de Historía da Sociedade e da Cultura 19 (January 2019): 329.↩

5. Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 57-58, 69-71.↩

6. Christina Zendt, “Marcos Zapata’s Last Supper: A Feast of European Religion and Andean Culture,” Gastronomica 10, no. 4 (2010): 11.↩